Peter Carr Biography and Conception Scenarios

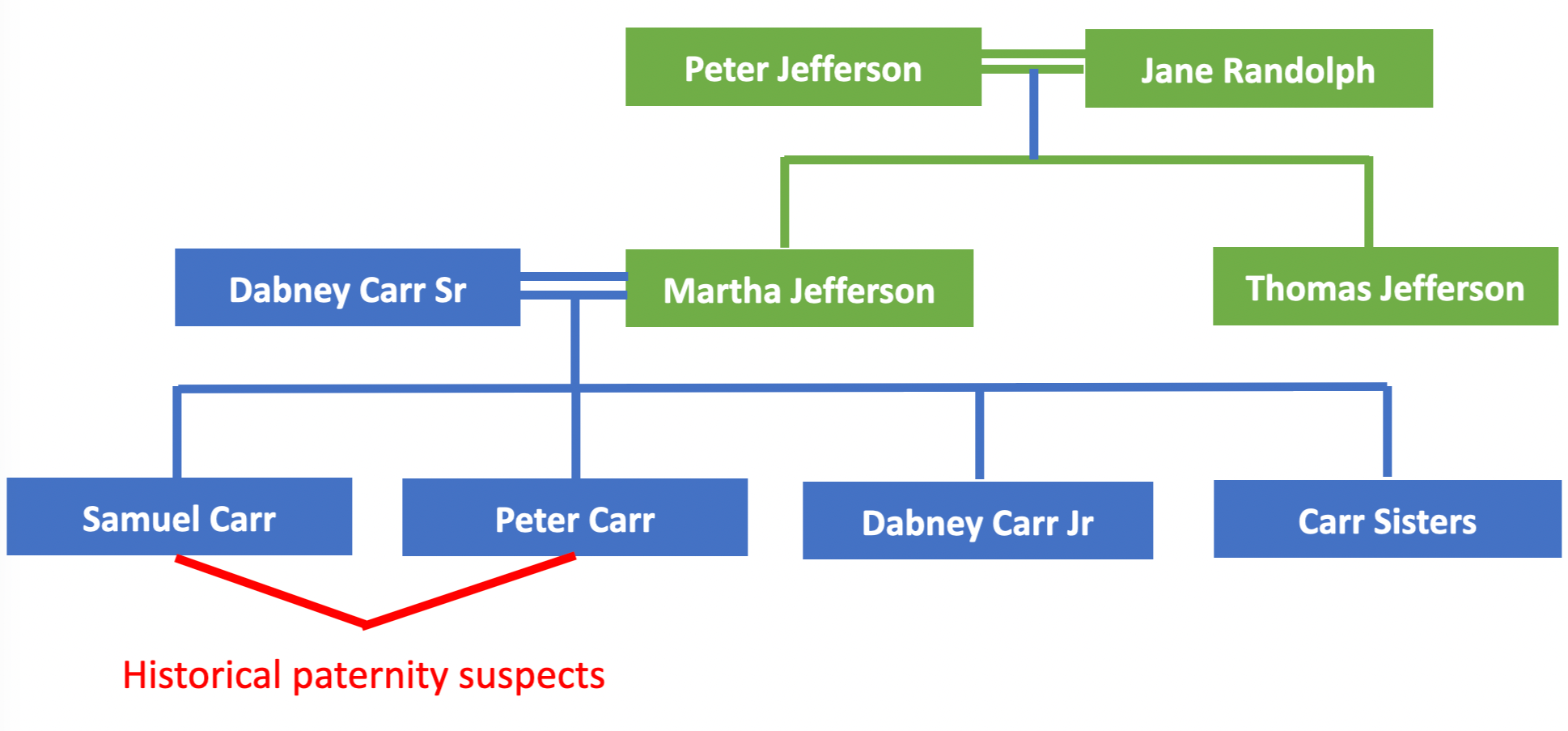

Historians had long pointed to the Carr brothers as prime suspects for paternity, particularly Peter Carr. In the 1998 study, the Carr male Y-DNA showed no match with Sally Hemings last son Eston Hemings, however it does not rule out that Peter Carr could have fathered previous children of Sally Hemings. According to the oral history passed down by Peter Carr descendants: “Peter Carr and Sally Hemings had a loving affair in her cabin on Mulberry Row and had all their children there. Their relationship lasted over a decade.”

This bio pieces together Peter Carr’s life in the context of his relationship with his uncle Thomas Jefferson, as well as with Sally Hemings, with added focus on the conception windows for Sally’s children.

Peter Carr

(1770-1815)

Peter Carr’s father Dabney Carr (Sr.) was a lawyer, statesman and best friend of his boyhood schoolmate Thomas Jefferson. The familial bond between the two friends became even stronger when Dabney married Jefferson’s sister Martha. The couple gave birth to their first son Peter on January 2, 1770. A month later Jefferson wrote in admiration to a friend that Dabney “speaks, thinks, and dreams of nothing but his young son.”1

Dabney Carr and Jefferson had formed so close a friendship that in their youth they made a vow that whoever should first pass away first, the surviving friend would bury the other under the oak tree where they regularly sat and studied together. The tree was on the side of the mountain upon which Jefferson would later build his house, the future Monticello.

Three years after his son Peter’s birth, Dabney Carr suddenly passed away at the age of 29 in 1773. Jefferson was devastated when he learned the news and heard that his friend had already been buried. Jefferson arranged to have Dabney’s body disinterred and brought to Monticello where he buried his best friend under the oak tree in what was later to become the Jefferson family cemetery at Monticello. Jefferson wrote on his gravestone:

HERE LIES THE REMAINS OF DABNEY CARR... LAMENTED SHADE! WHOM EVERY GIFT OF HEAVEN PROFUSELY BLEST, A TEMPER WINNING MILD. NOR PITY SOFTER, NOR WAS TRUTH MORE BRIGHT; CONSTANT IN DOING WELL. HE NEITHER SOUGHT NOR SHUNNED APPLAUSE. NO BASHFUL MERIT SIGHED NEAR HIM NEGLECTED; SYMPATHISING HE WIPED OFF THE TEAR FROM SORROW’S CLOUDED EYE, AND WITH KINDLY HAND TAUGHT HER HEART TO SMILE. TO HIS VIRTUE, GOOD SENSE, LEARNING AND FRIENDSHIP. THIS STONE IS DEDICATED BY THOMAS JEFFERSON, WHO OF ALL MEN LOVED HIM MOST.

After Dabney’s death, Jefferson brought his widowed sister Martha Carr and her five children to live with him at Monticello. Six years prior to their arrival, Jefferson’s only son had died in infancy. Having witnessed the love that Dabney had for his son Peter, it may have endeared and committed Jefferson to take a deferential liking to Peter. Jefferson took personal responsibility for and a special interest in the education of Peter and Dabney’s youngest son, Dabney Jr.. Jefferson described himself as Peter’s preceptor and Peter later became known among the family as Jefferson’s favorite nephew, and even a surrogate son.2 3

Just two weeks after Dabney’s death, Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayles also died, leaving Jefferson and his wife property and 135 slaves, along with heavy financial debt of £4,000 (the equivalent of $800,000 in today’s currency) 4. It was believed that later in his life, Wayles had fathered the last six children of his slave Elizabeth “Betty” Hemings, who had a total of twelve children. After Wayles’ death there was an effort to keep the large Hemings family intact by bringing them all to Monticello together. Sally Hemings was the youngest of the siblings, arriving at Monticello as a one-year-old infant while Peter had recently arrived at the age of three.

Peter, his four siblings, and Jefferson’s two daughters all enjoyed an idyllic childhood growing up together at Monticello. Memorable events included foot races organized by Jefferson who also was known to climb up cherry trees to drop the ripe fruit down into the aprons and hats of the children.5 The boys went swimming and fishing in the nearby Rivanna River and could go hunting through the Albemarle countryside. Tamed deer would eat from Jefferson’ hands. Music was regularly in the air, with Jefferson daily practicing on the violin. And there was no shortage on interesting guests passing through to provide fascination.

The children were educated often personally by Jefferson at Monticello when they weren’t at nearby schoolhouses. Jefferson’s eldest daughter Martha described how her father “bestowed much time and attention on our education — our cousins, the Carrs, and myself....” 6 Jefferson’s immense library was at hand, with such works available as Don Quixote, Shakespeare, the Iliad, Greek and Roman literature and fables. The Carr boys attended the same neighborhood school that Jefferson and their father Dabney Carr had previously attended.

When Jefferson traveled to Paris to serve as Minister to France in 1784, he debated whether to bring Peter with him.7 He eventually decided against it and sent Peter to boarding school. He implored his younger friend James Madison to take temporary guardianship of Peter. In a letter to Madison he articulated the personal and sentimental significance of the boy:

I have a tender legacy to leave you on my departure. I will not say it is the son of my sister, though her worth would justify my resting it on that ground; but it is the son of my friend, — the dearest friend I knew, — who, had fate reversed our lots, would have been a father to my children. He is a boy of fine dispositions, and of sound, masculine talents. I was his preceptor myself as long as I staid at home....8

While Jefferson wrote letters advising many young men, in no others does the interest and affection deepened by a sense of responsibility appear as in those to this nephew Peter.9 He hoped the education he planned for Peter was “to render you precious to your country, dear to your friends, happy within yourself.”10 Jefferson personally mapped out Peter’s curriculum and extensive reading list and asked others to watch over him and his progress. During Peter’s adolescence at boarding school, Jefferson wrote to him to impart the value of education and to treat his teachers with the utmost respect.11

Despite Jefferson’s best intentions, Peter was a free spirit who began to stray from Jefferson’s well-planned trajectory of steely personal discipline. Two years after Jefferson left for France, he received distant reports that Peter had not been attending his classes at William and Mary College. Jefferson wrote Peter a strong letter in 1785 where he appeared worried about Peter’s deviation and tried to appeal to his conscience and higher commitment to truth:

“Give up money, give up fame, give up science, give the earth itself and all it contains rather than do an immoral act. And never suppose that in any possible situation or under any circumstances that it is best for you to do a dishonourable thing however slightly so it may appear to you. Whenever you are to do a thing tho’ it can never be known but to yourself, ask yourself how you would act were all the world looking at you, and act accordingly. Encourage all your virtuous dispositions, and exercise them whenever an opportunity arises, being assured that they will gain strength by exercise as a limb of the body does, and that exercise will make them habitual.” 12

Jefferson seemed to hope that in his absence, books would impart upon Peter not only wisdom but also morals. Jefferson sent books to Peter on numerous occasions, even from France. “The course of reading Jefferson proposed for his nephew would today stagger a more advanced scholar – let alone a fifteen-year-old high school boy – though perhaps Jefferson was abiding by the theory that a man's reach should exceed his grasp.”13 The books were to be read in the original language and would include Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon's Anabasis, Arrian, Quintus Curtius, Diodorus Siculus, and Justin. In Greek and Latin poetry, Peter was to complete Virgil, Terence, Horace, Anacreon, Theocritus, Homer, Euripides, Sophocles. From English literature Milton’s Paradise Lost, Shakespeare, Ossian, Pope's and Swift's works were recommended, while for morality Epictetus, Xenophon's Memorabilia, Plato's Socratic Dialogues, Cicero's philosophies, Antoninus and Seneca were suggested.14

After Peter finished his studies at William and Mary College, in May of 1789 he traveled to New York to join James Madison where a new government was being organized and George Washington had just been inaugurated as the first President. In October Peter traveled back to Virginia to begin studying law in Spring Forest.

Just two months later, Jefferson had finished his service as Minister to France and in December 1789 he returned to Monticello with his two daughters, along with James Hemings who had served as Jefferson’s chef learning French cuisine, and Sally Hemings who had served there as maid to Jefferson’s two daughters.15

In 1790 Peter moved back to his childhood haunts at Monticello to study law under Jefferson’s direction. Sometime in the fall of 1790, Jefferson wrote to his sister Martha that scurrilous accusations were made in local paper about Peter Carr and his cousin John Garland Jefferson by “a worthless fellow” named Rind. The original publication has not been found, and the nature of the accusations is unclear. Peter appeared to have convinced Jefferson that he was innocent, but John Garland Jefferson had to take temporary leave of Monticello.16 A few months later Jefferson answered a letter from John Garland Jefferson:

I think Mr. Carr and yourself have acted prudently in dropping your acquaintance with Mr. Rind. I am not acquainted with his character, but I hope and trust it is good at bottom; but it is not marked by prudence, and the want of this might often commit those who connect themselves with him. I hope that that affair will never more be thought of by any body, not even by yourself except so far as it may serve as an admonition never to speak or write amiss of any body, not even where it may be true, nor to countenance those who do so. The man who undertakes the Quixotism of reforming all his neighbors and acquaintances, will do them no good, and much harm to himself. 17

Peter survived the scandal and continued his post-graduate life at Monticello. Previously in their early upbringings when they first arrived at Monticello, Peter and Sally Hemings' childhoods had overlapped for nine years, and after six years of separation they were now residing together at Monticello as young adults.

Now 20 years old, Peter was three years older than Sally Hemings who was 17. Friends and relatives described how Peter was “peculiarly gifted and amiable.”18 “He was naturally eloquent. His voice was melody itself.”19 Being the son of Jefferson’s sister Martha Jefferson Carr, Peter had a physical appearance similar to both his tall and robust grandfather Peter Jefferson and uncle Thomas Jefferson, with “sandy colored hair” and “the advantage of a large and commanding figure.” 20 21 Sally Hemings too was “decidedly good looking” and said to be “mighty near white... very handsome, [with] long straight hair down her back.” 22 23

During Peter’s six years living as a young bachelor at Monticello (1790-1796), Peter and his brother Samuel developed a reputation for mixing with young mulatto slave women at Monticello.25 26

The oral history of Peter Carr descendants describes that Peter and Sally Hemings carried on a loving affair in her cabin and they had all their children there. Evidence that she lived in her own slave cabin on Mulberry Row 27 (below the main house)28 has been corroborated by Monticello archeologist Frasier Nieman, who points to the excavation of a French vase believed to have been brought back from France by Sally Hemings.29 The vase was excavated from the ruins of what Monticello labels as “servant’s house S”, which was constructed circa 1793.

Living within the privacy of her own dwelling, Sally Hemings gave birth to her first recorded child Harriet in October 1795 (died in 1797), conceiving the child around the month of January when she would have been 22 and Peter Carr 25. At that time, Jefferson was 51 years old and suffering serious physical decline, as noted in multiple correspondence spanning from September 1794 to April 1795. Jefferson wrote that his illness “finds me in bed under a paroxysm of the rheumatism, which has now kept me for ten days in constant torment and presents no hope of abatement.”30 He was so concerned about his deteriorating health that he wrote to friends stating: “My health is entirely broken down within the last eight months; my age requires that I should place my affairs in a clear state....” 31 This was a time in America when the average life span for men was under fifty.32 Jefferson would have been in a compromised state of health to conduct a sexual relationship during that conception period, whereas Peter would have been in his sexual prime and much more likely to be appealing in age and attraction.

In June of 1796, French writer Constantin François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney, visited Monticello for about 2 weeks. Volney wrote in his journal that he was astonished to see nearly-white slave children at Monticello. He described the uninhibited behavior of the Monticello slave women:

[W]omen and girls, both black and mulatresses being subjected do not have any censure of manners, living freely, either with the white workmen of the country [or] hired Europeans, Germans, Irishmen, and others which conditions differ little from their own." 33

Sally Hemings could likely have been one of the mulatress slave women who he observed mixing freely with the white men. That year there were only 5 or 6 female servants ranging from ages 13 to 61 at Monticello and in the vicinity. Sally Hemings, who would have been 24 at the time, and her sister Critta (aka Critty) were the only known young adult mulatresses other than the younger Betsy Hemings who was just 13 years old. Betty Brown, 37 years old and Nance, 35 years old (also daughters of Betty Hemings but may have had black fathers) were also at Monticello. Mary Hemings’ daughter Molly was also likely there that year. 34

Slave women having sexual relations with white men was not an uncommon occurrence in the south. A former South Carolina slave was once interviewed and asked what proportion of the enslaved young women had sexual intercourse before marriage, and answered: ''The majority do, but they do not consider this intercourse an evil thing. This intercourse is principally with white men with whom they would rather have intercourse than with their own color." 35

In August 1796, construction projects at Monticello prompted Peter to move four miles down the hill to nearby Charlottesville. It was three years since he had been admitted to the bar, and the career as a lawyer had failed to materialize in the way that Jefferson had hoped. There was a need for Peter to reinvent himself and find a livelihood.

On June 6, 1797, Peter married Esther “Hetty” Smith Stevenson, a widow with one son. Hetty was a member of a distinguished Baltimore family of wealthy merchants. One of her brothers was a US Senator from Maryland and another brother later served in both Jefferson's and Madison's cabinets.36 Hetty sold her property in Baltimore and invested the proceeds their Carrsbrook home soon after her marriage to Peter.

Jefferson returned to Monticello after having been away in Philadelphia on July 11th. It was the custom that he would alert his family and friends ahead of his arrival, and on the way he would often stop to pick up his daughter and her family at their Edgehill farm, if they hadn’t already gone ahead to Monticello. Monticello would then be reopened, and family and friends would flock to see him upon his return. It was a big event for extended family to come see their famous relative when he came back briefly to stay at Monticello. Peter was living nearby in Charlottesville, which was a short horse ride away. As Jefferson’s favorite nephew, he naturally had an open invitation and free access to visit Monticello to visit his uncle.

It was during this extended family gathering in July of 1797 that Sally Hemings conceived her second child, when she was 24 and Peter would have been 27. Jefferson would have been 54 at that time, and still struggling to recover from a painful bout of rheumatism. 37 Sally Hemings' second child, a son named Beverly, was born in April 1798, nine months after the large family gathering at Monticello.

After the birth of their first child in 1798, Peter moved his family to Carrsbrook, a 900-acre estate about 8 miles north of Monticello, where he and his wife Hetty would over the years give birth to eight children, including: Mary Jane (1798), Jefferson (1799), Dabney Smith (1802) Ellen (1806), Jane Margaret (1809). It was a short horse ride from Carrsbrook to Monticello, and with children to attend to, Hetty likely stayed home when Peter often rode to Monticello to visit. 38

Jefferson’s biographer Henry S. Randall conducted interviews with Jefferson’s oldest grandson Col. Thomas Jefferson Randolph (1792-1875). Randall wrote how Jefferson’s grandson described the two Carr brothers:

Col. Randolph informed me that Sally Hemings was the mistress of Peter, and her sister Betsey the mistress of Samuel and from these connections sprang the progeny which resembled Mr. Jefferson. Both the Heming girls were light colored and decidedly good looking. The Colonel said their connection with the Carrs was perfectly notorious at Monticello, and scarcely disguised by the latter never disavowed by them. Samuel’s proceedings were particularly open.39

Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge (1796-1876), who spent much of her youth at Monticello, would also describe the promiscuous behavior of the young men around Monticello, particularly that of Peter and Samuel Carr:

There were dissipated young men in the neighborhood who sought the society of the mulatresses and they in like manner were not anxious to establish any claim of paternity in the results of such associations.

One woman known to Mr. J. Quincy Adams and others as “dusky Sally” was pretty notoriously the mistress of a married man, a near relation of Mr. Jefferson’s, and there can be small question that her children were his....

Mr. Southall and himself being young men together, heard Mr. Peter Carr say with a laugh, that “the old gentleman had to bear the blame of his and Sam’s (Col. Carr) misdeeds.” 40

Peter likely made such a comment to Valentine Southall to impress and shock this younger man who was a frequent guest at Monticello. Since the accusations — which would later be leveled in the press against Jefferson — only named Sally Hemings and not her sister Betsey, Peter’s comment points to the possibility that both brothers might have had sexual relations with Sally Hemings. Other confessions were of the same tone: that both of them had relations with Sally Hemings.

Jefferson biographer Andrew Burstein noted that records verify the proximity of the Carr brothers to Monticello for Sally Hemings’ conceptions:

“Jefferson's Account Books show that both nephews [Peter and Samuel Carr] were either present at Monticello or having transactions with Jefferson during specific periods that correspond to Sally Hemings conceptions. Peter was 3 years older than Sally Hemings and had grown up as a favorite on his uncle's estate; Jefferson was 30 years older than Sally Hemings.” 41

Peter was ready by the end of the 1790’s to try to enter public service in the capacity of a member of the Virginia state legislature. He was a passionate political supporter of Jefferson and his Republican Party, but in his first foray into politics he stumbled out of the blocks in an incident that demonstrated Jefferson’s deference to his nephew Peter.

It has been revealed that under the pseudonym “John Langhorne,” Peter addressed a letter to George Washington (then of the opposing Federalist party) on September 25, 1797, in what appeared to be a sincere communication commiserating with Washington on alleged defamations directed at the former president in his retirement.42 After Washington dispatched a cautious reply,43 a local Federalist wrote to inform him44 and charged that author – possibly acting in league with Jefferson – had hoped to elicit an indiscreet response that would somehow reveal Federalist intentions.45 The incident dealt a final blow to Washington’s already deteriorating relationship with Jefferson but otherwise achieved nothing.46 Jefferson biographer Randall was informed who the author was, though he did not give his name, and said:

He was a young man, and was guilty of a highly improper and senseless prank; but he acted without the knowledge of anyone (unless perhaps of a person still younger and more thoughtless than himself) — [he] regretted it as soon as done — and most bitterly regretted it when he learned that it had been seized upon to hang a suspicion on Mr. Jefferson. 47

Whether the letter was a clumsy prank — for the group of young men in Albemarle County associated with Peter were capable of practical jokes — or whether it was a deliberate effort to gain political ends, it unfortunately helped finalize a growing breach between Washington and Jefferson.48 No records have been found to indicate that Jefferson reprimanded his nephew or that he tried to amend the situation with Washington, perhaps because in the process he would have had to expose his nephew as the author.

Jefferson must have forgiven him, because after Peter’s failed attempt to win election to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1799, Peter worked with Jefferson on his 1800 presidential campaign which was conducted mostly from his Monticello home.49 Jefferson was under scrutiny by the press and accused of many things, but it was still two years before the accusations of his mixing with Sally Hemings were first published (in 1802).

Sally Hemings was still living in her cabin when she conceived her third child sometime between July and September 1800,50 during the same time that Peter was regularly visiting Monticello to help with the campaign, most likely traveling alone by horseback from Carrsbrook. Sally Hemings' daughter Harriet (II) was born in May of 1801.

After Jefferson won the Presidential election, in March of 1801 he moved to Washington, DC, later bringing a few slaves from Monticello with him. However, it is noteworthy that he did not bring Sally Hemings, who remained at Monticello during his two terms of office, and there is no record of her ever traveling to Washington, DC.51

A month later, Peter Carr became a justice of the peace for local Albemarle County in Virginia on April 18, 1801. That same year he was elected to represent the county in the Virginia House of Delegates. He was beginning his career in public office, where he had to keep his reputation intact. While residing at Carrsbrook, Carr served in the House of Delegates for five terms.

In 1802, one year after Sally Hemings’ child Harriet II’s birth, salacious writer James Callender published accusations that Jefferson fathered children with his slave Sally Hemings who he described as “dusky Sally... the black wench and her mulatto litter,” and the “mahogany colored charmer,” “romping with half a dozen black men,” and a “slut as common as the pavement.” These descriptions were leveled even though Callender had never stepped foot at Monticello or interviewed anyone from there. His article began with the phrase “IT is well known that...” 52

Callender had previously spent years attacking the Federalists, the party in opposition to Jefferson, and a frustrated President Adams even sent Callender and other journalists to prison under sedition charges under the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson was strongly against imprisoning journalists and vacated all their charges when he came into office. Callender was freed, but he felt he was owed a government post which Jefferson refused to grant. The bitter Callender then turned against Jefferson and made it his mission to take down Jefferson with salacious attack articles.

Jefferson was dragged through the press, and an off-color poem to the tune of Yankee Doodle describing his slave relationship also spread by newspapers and pamphlets throughout the states.53 By his re-election year in 1804, the accusation that Jefferson was having an ongoing sexual relationship with his slave Sally Hemings had been circulating for two years and had become well known.

Back at Monticello, the salacious public accusations against Jefferson and the rumors about Peter being the culprit were causing great pain and embarrassment to Jefferson’s daughters and their families, particularly his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph, who “took the Dusky Sally stories much to heart.” She never spoke with her sons about the topic except on her deathbed, when she asked them to salvage the documents that proved that Jefferson and Sally Hemings were away from each other during at least one of the conception windows of her children, however those documents were lost. 54

On 17 April 1804, Jefferson’s daughter Maria “Polly” Jefferson Eppes died at the age of twenty-six. At this point in his life Jefferson had lost 5 of his 6 children, along with his wife. He had been extremely fond of Polly, and this was a significant loss for him. The funeral drew family and friends from all over Virginia to Monticello. Jefferson was grief-stricken and was joined by his last surviving daughter, Martha, who had played a key role years earlier to comfort and tend to him after the loss of his wife and his other children. While Jefferson was surrounded by the many who had come to mourn the loss of his daughter, it was during this period that Sally Hemings conceived her fourth child, Madison Hemings, who was born nine months later at Monticello on 19 January 1805.

Since it was repeatedly said by others and even confessed by Peter himself that he was the father of Sally Hemings' children, it is worth exploring the scenarios where Peter may have used the larger gatherings of family and friends as a cover to secretly join Sally Hemings in her cabin. Since the conceptions of Sally Hemings' other children occurred when Jefferson was at Monticello, it may have been the larger gatherings of people that may have provided cover for Peter to slip away from the crowd unnoticed, particularly when Jefferson was entertaining guests as the center of attention, or when the house was full of guests sleeping.55 Peter may have waited until everyone retired, then slipped out and walked from the main house down to Sally Hemings' cabin.

In addition to his patriarchal status with his extended family, Jefferson’s fame attracted large numbers of visitors — at times as many as fifty — and he felt obligated to accommodate them.

“Mr. Jefferson always made his appearance at an early breakfast, but his mornings were most commonly devoted to his own occupations, and it was at dinner, after dinner, and in the evening that he gave himself up to the society of his family and his guests.” 56

Jefferson would house guests in his home for weeks at a time, wherever space allowed. However, this only occurred when Jefferson was present at Monticello, as all other times the house was closed up. If Peter had come to visit Sally at Monticello when Jefferson wasn’t present and no guests were around, it would have been more noticeable and attracted more inquiry from overseers, slaves as well as full-time white immigrant workers.

Even though Peter lived relatively close by, he may have only consorted with Sally under such conditions to avoid being exposed. Leaving his wife with his children at his home in nearby Carrsbrook, he would have had the excuse of visiting Jefferson at Monticello and staying the night at his uncle’s home. If there was a large number of visitors at Monticello, Peter’s movements would not have stood out, since such large gatherings would have required the services of more servants who would have been occupied at the main house and less likely to notice him visiting Sally’s cabin, as “It took all hands to take care of [the] visitors.” 58

One of the most compelling eye-witness accounts at Monticello came from Captain Edmund Bacon, who noted seeing another man emerging early mornings from Sally’s cabin. In his Garden Book, Jefferson described Bacon as his Monticello overseer and before that working for him in various positions on the property.59 Back when Jefferson went to France, Bacon’s older brother was Monticello overseer. In his later years, Capt. Bacon dictated his memoirs in interviews with Reverend Hamilton Pierson, and while talking about Sally’s daughter Harriet, he stated that he saw not Thomas Jefferson, but another man coming out of Sally Hemings' cabin on many mornings:

“Mr. Jefferson freed a number of his servants in his will. I think he would have freed all of them if his affairs had not been so much involved that he could not do it. He freed one girl (Harriet) some years before he died, and there was a great deal of talk about it. She was nearly as white as anybody and very beautiful. People said he freed her because she was his own daughter. She was not his daughter; she was ____’s daughter. I know that. I have seen him come out of her mother’s [Sally's] room many a morning when I went up to Monticello very early.” 60

Rev. Pierson’s ministerial discretion omitted the name of the man that Capt. Bacon stated that he saw. Pierson justified the deletion by explaining that he did not want to cause pain to any surviving relatives. This was similar to how Jefferson’s biographer Randall also withheld Peter Carr’s name as the author of the infamous Langhorne letter, as well as how James Parton wrote in 1873, “The father of those children was a near relation of the Jeffersons, who need not be named.” 61

Regardless of who the man was who regularly emerged from Sally Hemings’ cabin, one thing is clear: Capt. Bacon stated definitively that it was not Thomas Jefferson he saw leaving Sally Hemings room many mornings, but another man.

A year after Madison Hemings’ birth, Peter Carr wrote to his sister Mary Carr on New Years Eve 1806: “I have hired Sary, and would thank you to desire Saml to send her over this evening.” 62 “Sary,” a nickname for Sarah, may have been Sally Hemings, and the Monticello research report gives her probable birth name as Sarah. Madison Hemings named his first daughter “Sarah.” Many of Jefferson’s slaves were allowed to move freely around the Charlottesville area, and some were loaned to family and friends for various services. This note from Peter is similar to others mentioned in correspondence noting that Sally Hemings was hired out as were many of her siblings from time to time. Her older sister Critty, a Monticello servant, married a free black man who lived near the Carrs in a “freestate” section of Albemarle, so presumably Sally Hemings visited her sister in that neighborhood too. If it was Sally Hemings, hiring her may have provided Peter with an opportunity to extricate her from Monticello, away from all its onlookers. 63

Jefferson biographer Randall relayed the conversation he had with Jefferson’s grandson Colonel Randolph who described confronting the two Carr brothers who shed tears of remorse about the public furor over Jefferson’s supposed infidelity:

Colonel Randolph said that a visitor at Monticello dropped a newspaper from his pocket or accidentally left it. After he was gone, he (Colonel R.) opened the paper and found some very insulting remarks about Mr. Jefferson’s Mulatto Children. The Col. said he felt provoked. Peter and Sam Carr were lying not far off under a shade tree. He took the paper and put it in Peters hands, pointing out the article. Peter read it, tears coursing down his cheeks, and then handed it to Sam. Sam also shed tears. Peter exclaimed, “arnt you and I a couple of — pretty fellows to bring this disgrace on poor old uncle who has always fed us!” 64

This second confession has been confused by some to be the same confession referred to in Ellen Coolidge’s letter, where she described how Peter may have been bragging to Mr. Southall — who was a younger contemporary of Peter — “say[ing] with a laugh, that ‘the old gentleman had to bear the blame of his and Sam’s (Col. Carr) misdeeds.’” 65 However, in the scenario quoted above, Col. Randolph — Jefferson’s grandson —was scolding the two Carr brothers and forcing them to acknowledge their transgressions that brought pain to their uncle and the wider family. Therefore, these seem to be two separate admissions. Historian Douglas Adair: “Peter Carr must have been conscious, long before Callender made Sally Hemings' name notorious, that this affair was only the most obvious and sensational way in which he had disappointed Jefferson's hopes and plans for his career.” 66

There also appears to be a third admission. Biographer Henry S. Randall was also sent a letter in 1838 from someone describing a conversation they had had with a contemporary of Peter Carr:

More than 20 years ago, the late Francis B. Dyer—a native of Albemarle and a worthy member of the Charlottesville Bar—told me that P… C… used to say that his was the sport and deviltry, while the uncle had the credit or blame.67

After the birth of Madison Hemings, Peter appears to have had no further children with Sally. Perhaps the relationship came to an end or was brought to an end. Did someone else in the family draw a line? Or was there simply a falling out between Peter and Sally? Did Peter's wife Hetty find out and insist that he end the relationship with Sally in order to fortify their marriage? Such an affair would need to be kept absolutely secret in order to not only protect their reputation, but also by extension the reputations of Hetty’s two brothers who held high federal positions, as such rumors could potentially cause them serious political problems. It appears Peter was able to preserve his marriage to Hetty: upon his death, Peter’s will bequeathed "to my excellent and beloved wife all my estate whatsoever and wherever during her life...” 68

Peter's mother, Martha Jefferson Carr, died in 1805, a year after Madison Hemings’ birth and before the birth of Sally Hemings’ last child Eston. Could his mother have appealed to Peter on her deathbed for him to end the relationship, rumors of which might have caused pain and embarrassment to her brother Thomas and the family?

Sally Hemings’ last son Eston was conceived sometime between 15 August and 12 September 1807. The 1998 y-DNA study showed no genetic match between Eston Hemings and Carr descendants, however it showed a y-DNA match with 25 Jefferson males who were alive at the time. Jefferson’s brother Randolph would also have carried that matching y-DNA, and evidence has points to him as a likely candidate for the paternity of Eston.69

Jefferson’s brother Randolph was known at Monticello as “Uncle Randolph,” and could also have been referred to as “Uncle Jefferson.” In 1976, a descendant of Eston Hemings told The Washington Post of her family’s oral history: “We were told we were related somehow to an uncle of Jefferson’s.” 70 71

Randolph Jefferson rode and served with four militiamen who had black slave mistresses, including one man whose mistress was Mary Hemings, one of Sally's sisters.72 Randolph was invited by Jefferson to join him and Randolph’s twin sister Anna 73 at Monticello in the late summer of 1807, nine and a half months before Eston’s birth.74

While Thomas Jefferson entertained relatives and guests with intellectual discussions and music in the main house at Monticello — similar to Peter Carr — Jefferson’s brother Randolph may have slipped out unnoticed to Sally Hemings’s cabin. He was said to be “an unenlightened dirt farmer” 75 who “imbibe[ed] alcoholic beverages,”76 and not interested in Jefferson’s political life.77 A Monticello slave described how Randolph was known to “come out among black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night,” and “hadn't much more sense than” the slave himself.78

Just days after news spread of Eston’s birth, Randolph appeared uninvited at Monticello. During that visit Randolph was joined by his adult legal children and was assisted by his brother Thomas to draft Randolph’s will, stipulating that all his property be bequeathed to his legal [white] children. Could Randolph’s adult children have been insisting on the drafting of a will because of their concern of potential competing claims to his inheritance from Sally’s child Eston?

Shortly after Eston’s birth in 1808, Sally Hemings was moved out of her cabin to live with her sister Critta in the south colonnade of the main Monticello house, possibly to protect her from any paramours.

In 1809, Jefferson’s term as president ended and he returned from Washington to spend the rest of his life in retirement at Monticello. After his return, and throughout his remaining 17 years, Sally Hemings had no further children, which contradicts the notion that he moved her into the main house complex to continue a sexual relationship with her. Sally would have been 36 years-old and still of child-bearing age, since both her mother Betty and sister Betty Brown each had children until the age of 42.

The same year, Randolph remarried to a younger, controlling wife named Mitchie Pryor. In 1815 he conceived a son with her, John Randolph Jefferson, confirming that his virility would have still been intact at the time of the 1807 conception of Eston Hemings.

Peter Carr, despite his widely acknowledged gifts, failed to realize Jefferson’s hopes for him to achieve a distinguished legal or political career, at least in part because of his self-indulgence and indolence which he stood accused of in an otherwise affectionate memoir by a much-younger cousin. 79

Peter did, however, collaborate in perhaps the greatest project of Jefferson’s retirement: the promotion of education and the eventual creation of the University of Virginia and shaping of public schooling in America.

After his political defeat in 1809, Peter turned his classical education to practical advantage by running a private school at Carrsbrook. The school, which opened in 1811, accommodated seventeen boys, including a score of day students, until it closed several years later.

In Jefferson’s travels to Europe he observed various universities and contemplated what would make an ideal higher education for the youth of Virginia post Revolution. It was the mature Peter who became the “depository” of Jefferson’s ideas on education. Some of Jefferson's most famous dicta —on religion, on travel, as well as on education— were addressed to Peter in a famous letter of September 1814. Their common interest in learning was a continual bond between them. 80 81

Carr's experience as both an educator and legislator made him a logical candidate for appointment in 1814 as a trustee of the infant Albemarle Academy, the forerunner of the University of Virginia. Elected president of the trustees, Carr assisted Jefferson in drafting plans for the government of the school and for financing its erection and support. He and Jefferson also drafted a petition asking for an appropriation from the General Assembly for the institution. It was his involvement with Jefferson on this project which occasioned the oft-cited letter which Jefferson outlined his plan for a comprehensive system of public education for Virginia, which would become a blueprint for the public school system in America.

The War of 1812 had escalated and now was at Virginia’s doorstep. After the British army burned Washington in August 1814, Peter joined the contingent of militia guarding the approaches to Richmond. The British moved instead against Baltimore, and he returned home, but the rigors of service in a cold and wet encampment compromised his health. Two weeks after complaining to Jefferson of rheumatism, ague, and fever, Peter Carr died at Carrsbrook on February 17, 1815. 82

There is a mystery of how Jefferson reacted to Peter Carr’s death and whether his body was buried near his mother and father in the Monticello Cemetery as he requested in his will. 83

It was Jefferson’s usual habit to record family deaths in a prayer book and in his Memorandum Books; however, he could have been overcome with grief when Peter died in 1815. There is no entry in his records of Peter's death or burial. The lack of any entry is extremely unusual since Peter was most likely buried at the family cemetery at Monticello near his father and mother (as he requested in his will) in an unmarked grave. 84

A year after Peter’s death, Jefferson mentioned him in a letter to Peter’s brother, Judge Dabney Carr (Jr.). In the letter, Jefferson was reminiscing about the death of his childhood friend Dabney Carr (Sr.) who had passed away in 1773. After describing many of his positive attributes, he reflected on his passing and related it to Peter’s death:

“[T]o give to those now living an idea of the affliction produced by his death in the minds of all who knew him, I liken it to that lately felt by themselves, on the death of his eldest son, Peter Carr, so like him in all his endowments and moral qualities, and whose recollection can never recur without a deep-drawn sigh from the bosom of anyone who knew him.” 85

Peter Carr was eulogized by his friend William Wirt, who wrote: “No man was dearer to his friends; and there was never a man to whom his friends were more dear.”

ADDENDUM

Did Jefferson know? Or did he not want to know?

The Report of the Scholars Commission explored the question of whether other men could have had sexual access to Sally Hemings without the knowledge of Thomas Jefferson.

[I]t is certainly easy to conceive how such a relationship might have gone on without his specific knowledge. Monticello was usually crowded with visitors, and Jefferson’s practice of enchanting his guests with after-dinner conversation is well established. His far less cerebral brother, Randolph, is said to have preferred spending his evenings at Monticello playing his fiddle and dancing among the slaves. There is no reason to assume that, while Thomas Jefferson was occupied entertaining visitors, others — be they Randolph, one of his sons, or perhaps one of Jefferson’s other nephews from the Carr family — could not have been exploiting the women in the slave quarters. This could have had aspects of mutual affection, violent rape, or simply acquiescence to the inevitable by a slave woman who felt powerless to resist—we just do not know. It may have occurred behind Thomas Jefferson’s back or with his general knowledge. Given his well-established opposition to miscegenation86 and the sexual exploitation of slave women,87 not to mention his professed belief that slave holders had a moral duty to treat their slaves with dignity,88 it is difficult to assume that it occurred at Monticello with his blessing. 89

Jefferson’s biographer Randall discussed with Jefferson’s grandson, Colonel Jeff Randolph, the possibility that Jefferson may have been insulated from news of the sexual activity of the Carr brothers at Monticello:

I asked Col. [Jeff] Randolph why on earth Mr. Jefferson did not put these slaves who looked like him out of the public sight by sending them to his Bedford estate or elsewhere, — He said Mr. Jefferson never betrayed the least consciousness of the resemblance — and although he (Col. Randolph) had no doubt his mother (Jefferson’s daughter Martha Randolph) would have been very glad to have them thus removed, that both and all venerated Mr. Jefferson too deeply to broach such a topic to him. What suited him, satisfied them. Mr. Jefferson was deeply attached to the Carrs — especially to Peter. He was extremely indulgent to them and the idea of watching them for faults or vices probably never occurred to him. Do you ask why I did not state, or at least hint the above facts in my [biography] Life of Jefferson? I wanted to do so. But Colonel Randolph, in this solitary case alone, prohibited me from using at my discretion the information he furnished me with. When I rather pressed him on the point, he said, pointing to the family graveyard, “You are not bound to prove a negation. If I should allow you to take Peter Carr’s corpse into Court and plead guilty over it to shelter Mr. Jefferson, I should not dare again to walk by his grave: he would rise and spurn me.” 90

Did Jefferson know of the relationship and allow it to continue, or was he unaware? Jefferson may have been deferential to Peter Carr to a fault, possibly turning a blind eye. Or was such information kept from him, to not cause him pain and embarrassment, as his grandson described?

When Peter precipitated the final falling out between Jefferson and Washington with his “John Langhorne” letter stunt, Jefferson could have cleared his own name and salvaged his relationship with Washington by exposing his nephew Peter as the culprit who operated independently. However, Jefferson kept silent. He had made it his mission to raise and protect the son of both his deceased best friend and his own widowed sister.91 Jefferson may have been willing to sacrifice his own public character to protect Peter’s character, as well as protect his widowed sister Martha Jefferson Carr, whom Jefferson took in to live at Monticello after the passing of her husband Dabney Carr.

Jefferson always strove to overlook the bad and only see and encourage the good in people. His family members knew him as an eternal optimist, invested in fostering the positive image of others, advising “never to speak or write amiss of any body, not even where it may be true, nor to countenance those who do so.”92 Just as there was an effort to avoid the topic with Jefferson, there was likely an effort to also shield Jefferson’s widowed sister (Peter’s mother) Martha Jefferson Carr from the rumors. Jefferson wrote to his brother after her passing: “she had the happiness, and it is a great one, of seeing all her children become worthy & respectable members of society & enjoying the esteem of all.”93 After all, Peter later contributed to Jefferson’s inspiration for establishing a school of education, which ultimately led to the historic creation of the University of Virginia.

Lastly, it is likely that Sally Hemings and five of her fourteen brothers and sisters were the children of Betty Hemings and John Wayles, who was the father of Jefferson’s wife Martha Jefferson. This is believed to be the reason why the wider Hemings family — not just Sally’s children — had special privileges at Monticello, and a number of them were either allowed to run away or were legally freed along with property and money.94 In addition to protecting Peter Carr, Jefferson’s silence may have also been protecting Sally Hemings by absorbing the accusations and shielding both of them from public ridicule and scorn.

“I was constantly exposed to see the most cruel slanders against my dear father circulated and in many instances deceiving good and honorable men, who were not sufficently (sic) acquainted with his private character to understand how impossible it was for there to be any truth in them, but who knew him only through the medium of the bad passions which party spirit excites & which like the jaundice, colours every object...” [95][1]

“...he is so good himself, that he can not understand how bad other people may be.” 96

1 Thomas Jefferson to John Post, 21 February 1770, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0023

2 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, May 8, 1784; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-07-02-0179

3 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

4 Currency conversion using University of Wyoming’s Historical Conversion of Currency calculator: https://www.uwyo.edu/numimage/currency.htm

5 Jane Blair Cary Smith, "The Carysbrook Memoir," p. 69, The Carys of Virginia, ca. 1864, Accession #1378, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

6 Kevin J. Hayes, Jefferson in His Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of His Life, Drawn from Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and Associates, 2012

7 Mrs. George P. Coleman, contributor, "Randolph and Tucker Letters,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. XLII (October, 1934), 318-320. Thomas Jefferson to Walker Maury. Paris, August 19, 1785; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-08-02-0321

8 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, May 8, 1784; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-07-02-0179

9 Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr., John Wayles Eppes, and John Bannister, Jr., received letters about the same time as Peter Carr. They are printed in the Lipscomb and Bergh edition of his Writings.

10 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, Paris, August 20, 1787. Jefferson, Writings. VI, 262.

11 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 11 December 1783. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-06-02-0302

12 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, 19 August 1785; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-08-02-0319

13 Elizabeth Dabney Coleman, The Carrs of Albemarle, UVA 1944. https://doi.org/10.18130/V3FB4WK8J

14 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr. Paris, August 19, 1785.

15 Despite Madison Hemings’ claims, there is no evidence that Sally Hemings returned from France either pregnant or carrying an infant child, and no such child was listed on the ship manifest. The allegations that Sally gave birth around this time to a boy named Tom Woodson who resembled Thomas Jefferson have been proven false. A 1998 DNA study showed no match at all between Jefferson or Woodson descendants, and subsequent DNA analyses have shown no connection at all between Woodson and Hemings descendants.

16 Letter from Thomas Jefferson to (sister) Martha Jefferson Carr, November 7, 1790. It is suspected that Rind was probably James Rind, son of the Williamsburg printer, who was a lawyer and a duellist in Richmond between 1792 and 1804. He was known as “a clever letter writer”. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-18-02-0014

17 Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Garland Jefferson, 5 February 1791. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-19-02-0029

18 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

19 Coleman, Elizabeth Dabney, The Carrs of Albemarle, UVA 1944, p.34 (quote of William Wirt).

20 Cythia H. Burton,* Jefferson Vindicated*, 2005, p.19

21 Carr-Carey Papers. Obituary of Peter Carr by William Wirt. February 17, 1815.

22 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

23 Jefferson, Isaac Granger, Memoirs of a Monticello Slave: As Dictated to Charles Campbell in the 1840’s by Isaac, One of Thomas Jefferson’s Slaves, 1951, p.10.

24 Peter Carr (1770–1815), Encyclopedia of Viriginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/carr-peter-1770-1815/

25 Letter from Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge (October 24, 1858). (emphasis added) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-ellen-wayles-randolph-coolidge-to-joseph-coolidge-october-24-1858/

26 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

27 Slave Housing, Historical Marker Database. https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=100176

28 Discovering Mulberry Row (historical marker). https://monticello-www.s3.amazonaws.com/files/old/legacy_files/mr/media-pdfs/G-03%20Process%20Panel_PRINTABLE.pdf?bigtree_htaccess_url=sites/default/files/legacy_files/mr/media-pdfs/G-03%20Process%20Panel_PRINTABLE.pdf

29 Monticello: “Archaeologists found this ceramic jar with a French Label at a slave dwelling site on Mulberry Row. Sally Hemings may have owned this jar.” https://www.monticello.org/sallyhemings/

https://www.historypin.org/en/explore/geo/37.77493,-122.419416,12/bounds/37.683422,-122.49838,37.866325,-122.340452/paging/1/pin/1145912

30 Thomas Jefferson to Edmund Randolph, 7 September 1794. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-28-02-0109

31 Jefferson to James Madison, 27 April 1795, DLC.

32 Decennial Life Tables for the White Population of the United States, 1790–1900. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2885717/

33 Gaulmier, Jean, Un gran temoin de la revolution et de l'empire, Volney, (Paris, 1959), 211, translation.

34 Randall, Henry S., Life of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 3, p672.

35 Blassingame, John W., Slave Testimony, Two Centuries of Letters, Speeches, Interviews, and Autobiographies, LSU Press, 1977, p.376.

36 Adair, Douglas. Fame and the Founding Fathers: Essays. The Jefferson Scandals. 1960. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/cron/1960scandal.html

37 Thomas Jefferson to Mary Jefferson, 25 May 1797. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-29-02-0313

38 ---

39 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

40 Letter from Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge (October 24, 1858). (emphasis added) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-ellen-wayles-randolph-coolidge-to-joseph-coolidge-october-24-1858/

41 Burstein, Andrew. The Inner Jefferson, Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1995.

42 Letter from John Langhorne (Peter Carr) to George Washington (September 25, 1797). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-john-langhorne-peter-carr-to-george-washington-september-25-1797/

43 Letter from George Washington to John Langhorne (Peter Carr) (October 15, 1797). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-george-washington-to-john-langhorne-peter-carr-october-15-1797/

44 Letter from John Nicholas to George Washington (November 18, 1797). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/letter-from-john-nicholas-to-george-washington-november-18-1797/

45 Party insights which could presumably be used against them by Jefferson’s opposing party (Republicans).

46 Looney, J. & Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Peter Carr (1770–1815). (2021, December 22). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/carr-peter-1770-1815

47 Randall, Life of Thomas Jefferson; Vol. II 373.

48 Looney, ibid.

49 Looney, ibid.

50 Harriet II’s birthdate was only listed without the day and only by month and year (May 01). Therefore the birth could have taking place in a 31-day window, thus allowing for an 8-week conception window rather than the typical 4-week window.

51 Bacon, Captain Edmund and Pierson, Rev. Hamilton W., Jefferson at Monticello. The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson. From entirely new materials...,1862. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moa/ABP5340.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext

52 “The President, Again” by James Thomson Callender (September 1, 1802). https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/the-president-again-by-james-thomson-callender-september-1-1802/

53 A SONG, SUPPOSED TO HAVE BEEN WRITTEN BY THE SAGE OF MONTICELLO, Boston Gazette, 1802. https://presidents.ub.uni-freiburg.de/config/presidents/poem.php?docid=bib_208

54 Parton, James, FLOWER, p237-8; Henry Randall writes about Jeff Randolph’s 1868 letter to James Parton, Scholars Commission, p210. (emphasis added)

55 “[Jefferson’s grandson Col. Randolph] said Mr. Jefferson never locked the door of his room by day: and that he (Col. R.) slept within sound of his breathing at night.” Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868). Isaac Granger Jefferson, in his Memoirs of a Monticello Slave (p.42), said he was in the main house and “slept on the floor in a blanket... in the out-chamber... in the south end of the house called the South Octagon — nearby Jefferson’s room where he slept.”

56 Randall, Henry S., Life of Thomas Jefferson, p.331.

57 Bacon, Captain Edmund and Pierson, Rev. Hamilton W., Jefferson at Monticello. The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson. From entirely new materials ..., 1862.

58 Randall, Henry S., Life of Thomas Jefferson, p.332.

59 Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book 601 (Edwin Morris Betts, ed., 1999)

60 Bacon, Captain Edmund and Pierson, Rev. Hamilton W.,* Jefferson at Monticello. The Private Life of Thomas Jefferson. From entirely new materials ..., 1862. p110. (emphasis added.) https://quod.lib.umich.edu/m/moa/ABP5340.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext

61 Parton, James, The Presidential Election of 1800,* The Atlantic Monthly, Vol. XXXII, 1873, p.29.

62 Peter Carr to Mary Carr, 31 December 1806, ViU; https://encyclopediavirginia.org/11467hpr-41c1a2f0f0b4ad8/

63 Burton, Cynthia H., Jefferson Vindicated, 2005, pp.22-24, 81. “Critty” or Critta was the first Monticello slave emancipated after Jefferson’s death. Her only child Jamey was, In addition to two of Sally’s children, Critta’s only child Jamey was one of at least two other light-skinned slaves who were allowed to “runaway”, each fitting the criteria of unqualified manumission laws

64 Letter from Henry S. Randall to James Parton (June 1, 1868) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-henry-s-randall-to-james-parton-june-1-1868/

65 Encyclopedia Virginia, Letter from Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge to Joseph Coolidge (October 24, 1858). (emphasis added) https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/letter-from-ellen-wayles-randolph-coolidge-to-joseph-coolidge-october-24-1858/

66 Adair, Douglas.* Fame and the Founding Fathers: Essays.* The Jefferson Scandals. 1960. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/cron/1960scandal.html

67 Letter from Nathanial Francis Cabell to Henry S. Randall, 17 December 1838, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

68 Albemarle County Will Book 6, p. 129.

69 Marshall, Eliot, Which Jefferson Was the Father?, Science, Vol 283, Issue 5399, 153-155, 8 January 1999.

70 Rosenfeld, Megan, Two Jefferson Lines Traced by Historian, The Washington Post, September 21, 1976, A1/A21.

71 People, November 23, 1998, “My parents told us we were related to Thomas Jefferson's uncle, which made us cousins removed several times.” -Julia Westerinen

72 Burton, Cynthia H., Jefferson Vindicated, 2005, pp.54, 60. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/pyoTAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=mistress+fosset

73 Randolph and Anna were twins, and Jefferson enjoyed seeing his brother and sister together: “This will enable me to pass two months at Monticello, during which I hope I shall see you and my sister there.” From The Domestic Life of Thomas Jefferson, Sarah N. Randolph, 1871, p. 137.

74 From Thomas Jefferson to Randolph Jefferson, 12 August 1807. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-6159

75 Mayo, Bernard, and Bear, James A., Thomas Jefferson and his Unknown Brother, University Press of Virginia, 1981, p. vii, 4.

76 Ibid, p.5, 32.

77 Thomas Jefferson to Randolph Jefferson, from France, 11 January 1789: “Dear Brother — the occurrences of this part of the globe are of a nature to interest you so little that I have never made them subject of a letter to you.” https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-14-02-0205

78 “Old Master’s brother, Mass Randall, was a mighty simple man: used to come out among black people, play the fiddle and dance half the night; hadn’t much more sense than Isaac.” -Isaac Granger Jefferson, Memoirs of a Monticello Slave: As Dictated to Charles Campbell in the 1840’s by Isaac, One of Thomas Jefferson’s Slaves, 1951.

79 Looney, ibid.

80 Thomas Jefferson to Peter Carr, Monticello, September 7, 1814. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-07-02-0462

81 National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination for Carrsbrook, 1981. https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/002-0011_Carrsbrook_1981_NRHP_Nomination.pdf

82 Looney, ibid.

83 Will of Peter Carr. https://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/14

84 Burton, Cynthia H., Jefferson Vindicated, 2005, p.39; Randolph, 63, 299-300; Will of Peter Carr, Albemarle Co. WB-6: 129-130; Hetty Smith Carr to Dabney.

85 Thomas Jefferson to [Judge] Dabney Carr [Jr.], 19 January 1816. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-09-02-0238

86 See, e.g., Jefferson to George Buchanan, Aug. 30, 1793, 26 Papers of Thomas Jefferson 788 (John Catanzariti, ed. 1995); Jefferson to Edward Coles, Aug. 25, 1814, 11 Works of Thomas Jefferson 416 (Fed. ed. 1905); and Jefferson to William Short, Jan. 18, 1826, 12 id. 434. Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia, Query XIV, in 2 Writings of Thomas Jefferson 201 (Mem. ed. 1903.)

87 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia, Query XVIII, in 2 Writings of Thomas Jefferson 225–26. (“The whole commerce between master and slave is a perpetual exercise of the most boisterous passions, the most unremitting despotism on the one part, and degrading submissions on the other. . . . If a parent could find no motive either in his philanthropy or his self-love, for restraining the intemperance of passion towards his slave, it should always be a sufficient one that his child is present.”)

88 Jefferson to Edward Coles, Aug. 25, 1814, 11 Works of Thomas Jefferson 416.

89 The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy, Report of the Scholars Commission, Edited by Robert F. Turner, 2011, p.196.

9 Parton, James, FLOWER, p238; Henry Randall writes about Jeff Randolph’s 1868 letter to James Parton, Scholars Commission, p210. (emphasis added)

91 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, May 8, 1784; https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-07-02-0179

92 Letter from Thomas Jefferson to John Garland Jefferson, 5 February 1791. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-19-02-0029

93 Thomas Jefferson to Randolph Jefferson, 6 September 1811. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-04-02-0122

94 Cythia H. Burton, Jefferson Vindicated, 2005, pp. 22, 165-166. The Jefferson-Hemings Controversy, Report of the Scholars Commission, Edited by Robert F. Turner, 2011, p.136.

95 Martha Jefferson Randolph to Ann C. Morris, Washington, May 31 1832. https://tjrs.monticello.org/letter/1232

96 Randolph, Sarah N., The Domestic Life of Thomas Jefferson, 1871, p.343